The Chromatic Scale and Fingering Maps

In the last few months, I’ve been writing about how jazz pianists play fast runs. This has encouraged me to revisit and update my article on ‘fingering maps’ and how they relate to idiomatic gestures, economical motion, and playing in different keys. The article below is similar to what I wrote in 2018, but with updated reflections on how pianists use spatial/directional relationships, and updated images that better communicate fingering/note clusters at the piano.

- The Chromatic Scale and Fingering Maps (550 words)

- Modifying Directional Relationships (220 words)

- Modifying Spatial Relationships (720 words)

- The Left Hand (130 words)

The Chromatic Scale and Fingering Maps

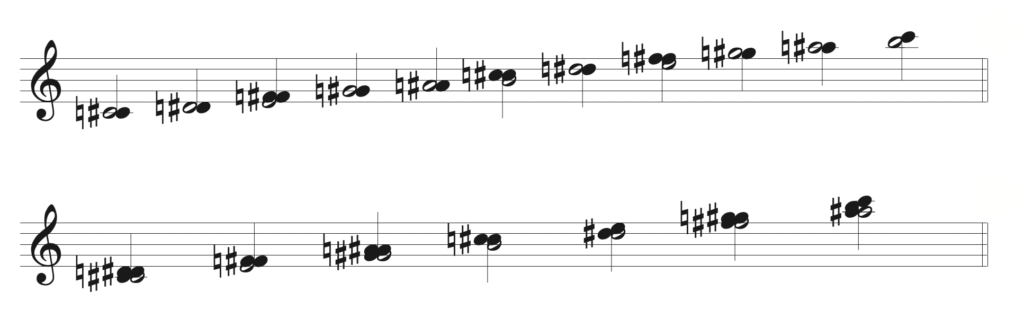

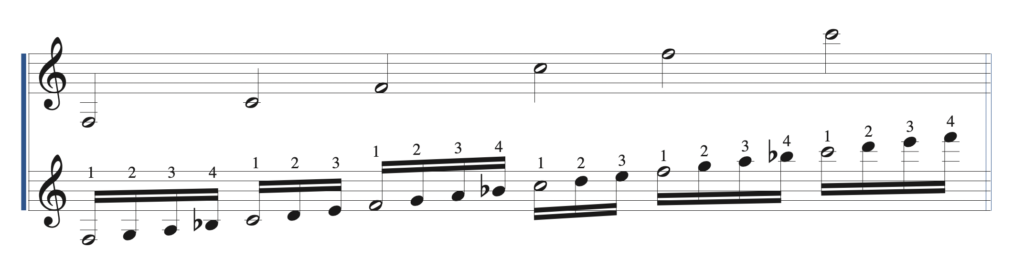

When it comes to fingering the chromatic scale, the following is common among my piano students:

Fortunately, I was taught an alternative fingering at a young age – it’s much better:

Why is it better? The two fingering examples above demonstrate variation in economy of motion. The second example is superior because it uses less hand positions and the thumb crosses over less often. As well as being more economical, it also allows the pianist to play it faster and with more precision and control.

It’s important to understand that pianists use note clusters, hand positions, and higher levels of abstraction to physically chunk groups of notes and spatial relationships. In many cases, pianists are using hand shapes and note clusters to help play, improvise, and memorize more efficiently. This process of abstraction is especially important when pianists are playing something technically demanding. More ergonomic gestures and economy of motion helps conserve energy and prevents injury.

Trying to capture this process of abstraction is why I’ve been notating my examples like this. The thumb acts as a spatial and visual anchor for the hand and is represented with a clear note head. Hand positions and note clusters are beamed together as a single, physical chunk. This notation style isn’t perfect, especially with more complex transitions between clusters, but it’s still more representative of a pianist’s connection to space and movement at the piano. Occasionally, I also notate note clusters like this:

Fingering is more complex and unpredictable in an improvisatory practice, but it can still follow rules that make playing the piano more ergonomic and economical. If we dig a bit further into what makes this chromatic fingering better, we can assemble some rules that can be applied to improvising using all scales in all keys, while maintaining economy and ease of motion.

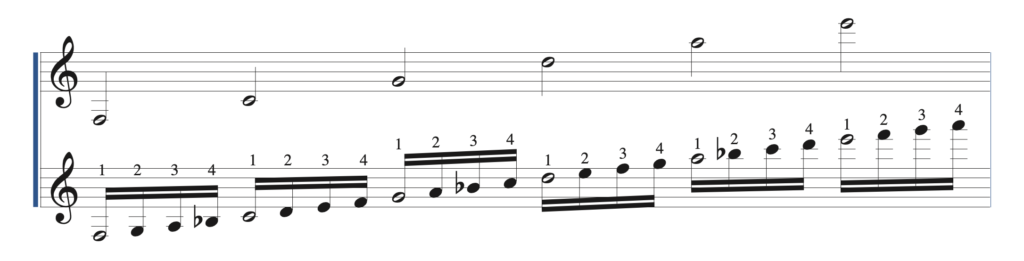

For example, one of the reasons this fingering is easy to play is because the thumb only plays white keys. If we order these thumb placements in the same manner as a scale (C-D-E-F-G-A-B), we get this sequence:

Another reason it’s easy to play is because from the thumb, we form 4-note and 3-note groupings. We can assemble 4-note and 3-note groupings on every white key:

The above is forming a hierarchy of hand positions. Using 4-note clusters will be more optimal than 2-note clusters. But sometimes 3-note or 2-note clusters are necessary to connect thumb positions (as in the chromatic scale). Good fingering will use a combination, with a preference for 4-note clusters because they offer the best economy of motion. So, to complete our fingering map, we can include 2-note clusters, at the bottom of the fingering hierarchy. (More on why 2-note and 3-note clusters are important below, when I look at the F Major scale)

What about 5-note clusters? 5-note clusters, (which include the 5th finger) aren’t included here because they’re limited in their range of motion. Crossing under the 5th finger is awkward and uncomfortable so playing the 5th finger in the right-hand likely leads to descending motion. Similarly, crossing over the thumb when playing a black key is also awkward and uncomfortable so playing the thumb on a black key leads to ascending motion. My fingering maps don’t include these possibilities because I prioritize the hand positions that preserve motion in both directions.

Modifying Directional Relationships

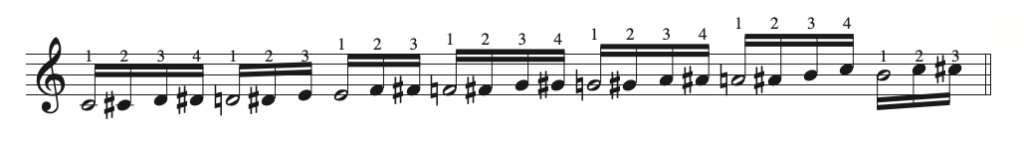

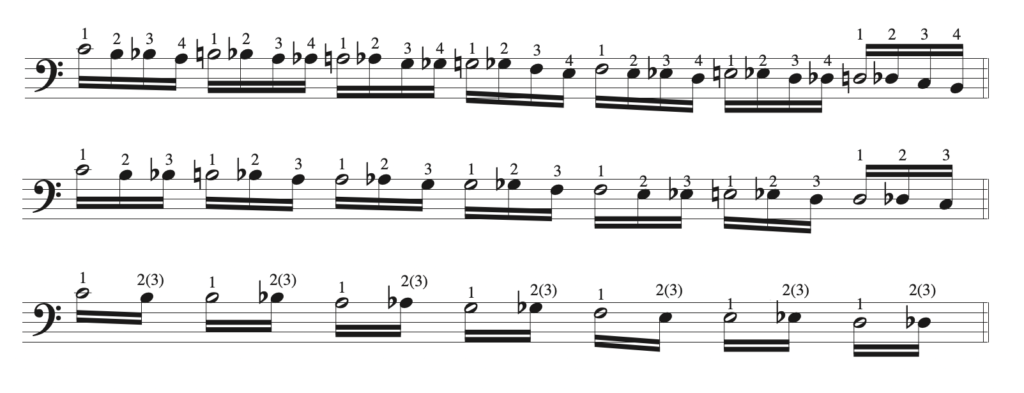

There are a number of ways we can expand on this. So far, the notes in these clusters have been ordered by ascending steps. They can also be reordered to include skips, direction changes, and descending motion. A few examples, using 4-note clusters:

These directional variations are physically simplified as a sequence of fingers (1-3-2-4)

(Away from the piano, these sequences can be also expressed though finger tapping on a desk or on your lap). At the piano, finger sequences combine with note clusters to form a unified chunk of physical information. This is important to consider when practicing/creating patterns and exercises. Variance in finger sequences combined with spatial variance is generally a good measurement of difficulty.

While note-to-note motion is varied in each of these examples, cluster-to-cluster motion is all ascending. I often use Schenkerian-like notation to express broad motion and directional relationships. For example, the above examples use this type of broad motion, resembling the C major scale:

Just as we can reorder note-to-note motion by adding skips and direction changes, we can do the same to this abstracted, deep structure.

Modifying directional relationships then, can occur on two level of magnification – Movement within note clusters and movement between clusters. This holistic picture sets the groundwork for exploring fingering maps and spatial relationships in more detail.

Modifying Spatial Relationships

Spatial relationships and ‘note clusters’ are characterized by the physical and visual distances between notes, and how they combine to create variations of black and white notes. There are two ways we can expand on this framework and modify spatial relationships.

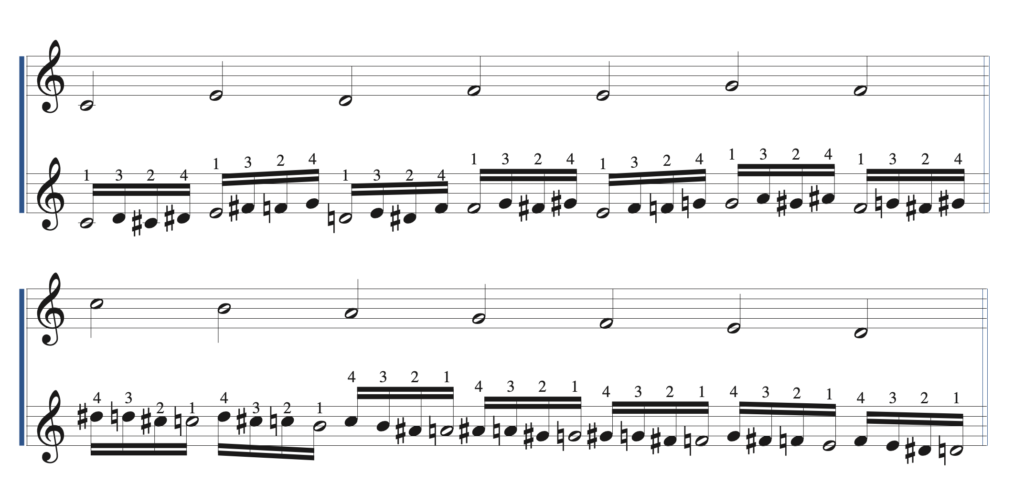

The first is to explore different intervallic relationships between notes. In all of the examples above, the notes within each cluster are spaced by three semitones (ST-ST-ST). One logical progression is to incorporate wider intervals into these clusters. Here are a few examples with various directional relationships. ST-WT-ST:

Here’s WT-WT-WT:

And lastly, using much wider intervals, P4-ST-M2:

The second is to use harmony and scales to define spatial relationships and patterns of black/white notes. Scales are simply unique spatial combinations of white and black notes at the piano. In the examples above, you may have noticed familiar note clusters and hand positions. The first example (ST-WT-ST) contains similar hand positions found in a diminished scale, or a harmonic minor scale. The second example (WT-WT-WT) has similar characteristics found in whole tone scales and major scales. And the last example (P4-ST-M2) is like a minor triad in 2nd inversion, with a b9.

While using anchor points and note clusters is still the best way to approach playing different scales, note clusters will vary in their intervallic relationships. For example, the F Major scale has six possible anchor points on F, G, A, C, D and E. A fingering map of the F major scale would look like this:

When we play the F Major scale ascending and descending, the traditional fingering uses a 4-note cluster starting on F, and a 3-note cluster starting on C.

Compare this to playing the F Major using only 4-note clusters:

This is an interesting exercise to practice, but it’s more difficult and not entirely practical. One reason is because playing the F major scale using 4-note and 3-note groupings keeps the scale spatially consistent each octave, which makes note clusters and crossovers easier to anticipate. Another reason is because of our tendencies to connect physical stability with harmonic stability. Our thumbs are drawn to ‘F’ because it represents the ultimate point of harmonic stability and the ‘beginning’ of the scale. If you were playing the G Dorian scale, the natural inclination would be to place the thumb on G, even though the note clusters and anchor points are the identical to the F Major scale.

Of course, aligning points of physical stability with points of harmonic stability isn’t always possible, like when playing the Db Major scale. Here’s the fingering map:

Two points of observations: The first involves the conflict that can exist between physical stability and harmonic stability. The thumb doesn’t always play consonant notes. In Db, with the thumb on C, harmonic consonance is in the 2nd finger. But harmonic consonance is in the thumb when it’s anchored on F. The feeling of harmonic stability is constantly moving around in the hand. Keeping track of this is one of the major points of practice for improvising pianists because every key/scale has a unique fingering map with varying connections between physical and harmonic stability. (We’ll see in later exercises that it’s also important to consider connecting points of physical stability with points of metric stability).

My second observation concerns the simplicity of this fingering map. While this makes playing the Db scale easier, it also makes it less useful. I’m reminded of this run by Art Tatum, from Humoreque:

These are the notes and note clusters from the Db Major scale, but with an added anchor point (B). This is one way to make scales more useful – add notes! I’m not suggesting Art Tatum’s added notes to scales to make them more useful, but he definitely knew where to place his thumb, regardless of harmonic context. With the ability to keep track of shifting harmonic stability in the hand, jazz pianists can ‘re-interpret’ any note cluster to fit a variety of chords and scales.

Whether you’re playing the Db major scale, Db major scale + B, a bebop scale, or a diminished scale, using fingering maps will lead to a better understanding of how harmonic relationships integrate with physical relationships. (I should also mention that despite all the example above, fingering maps apply to playing wider intervals too, not just step wise motion)

The Left Hand

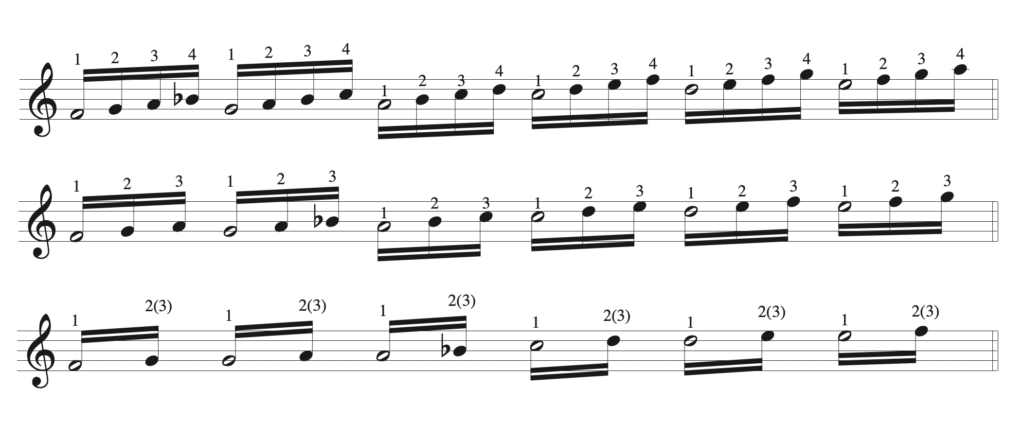

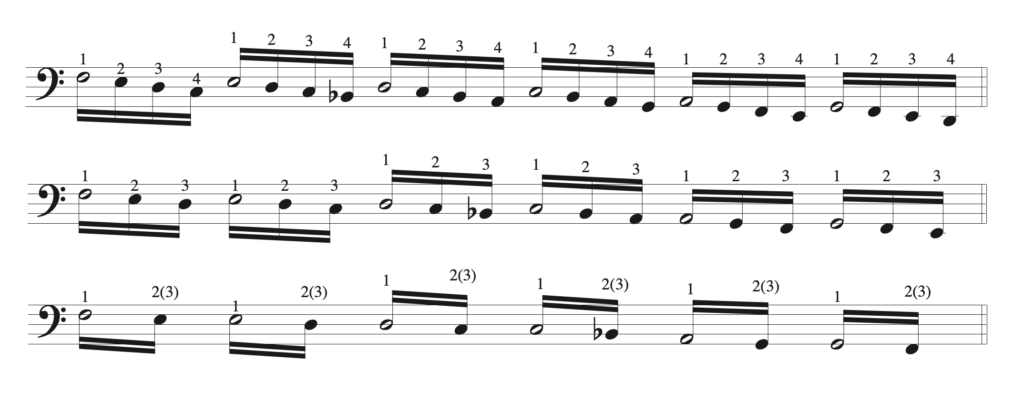

Discovering fingering maps for the left hand is straightforward. With the thumbs on white notes, we can easily create a finger mapping for the chromatic scale.

We can modify these fingering maps in the same way we modified them for the right hand – experimenting with various finger sequences, cluster-to-cluster motion, and wider intervals. Occasionally, pianists might encounter difficulties with these note clusters because in the left hand, they’re being spatially framed with the thumb from right-to-left. Harmony at the piano is predominantly framed from left-to-right. (More on spatial framing in my articles on Spatial Relationships, Directional Relationships, and Two-Handed Voicings)

Here’s the F Major scale:

In the next article, I’ll be exploring a scale’s finger mapping more thoroughly, with the focus on keeping track of harmonic consonance under the hand.